A Childhood Poem Comes Back To Heal

Another reminiscence of my childhood... Seems to be a theme lately.

I lay on my stomach, my hands covered in charcoal. The polished stone floor was shiny and I could see the individual pebbles that were embedded within it. The paper kept rolling up at the edges, and so I positioned my body on it lengthwise as best as I could to still be able to write. The door to the classroom was open and I could see all the other kids leaned over their desks working. Miss Elkington, my third-grade teacher walked around the room in her long skirt, her white hair piled into a bun on top of her head with wisps falling around her face. Every now and then she would crouch down to speak quietly to one of the kids.

I lay on my stomach, my hands covered in charcoal. The polished stone floor was shiny and I could see the individual pebbles that were embedded within it. The paper kept rolling up at the edges, and so I positioned my body on it lengthwise as best as I could to still be able to write. The door to the classroom was open and I could see all the other kids leaned over their desks working. Miss Elkington, my third-grade teacher walked around the room in her long skirt, her white hair piled into a bun on top of her head with wisps falling around her face. Every now and then she would crouch down to speak quietly to one of the kids.

“Write a poem about a place where you feel calm,” she told the class. Her writing lessons were my favorite part of the day. I could tell it was her favorite part of the day as well. She loved poetry and words and reading. She always asked what we were reading and I read voraciously that year, just so I could have a good answer. In the life of most kids, the year a family splits up might be considered a tumultuous year, but I don’t remember it that way. I loved going to Miss Elkington’s class. She was the steady constant for me that year. My sister and I moved out of our house to a tiny two-bedroom apartment across the park with my mom and Larry, a friend of my mom and dad’s who had been living in the third floor of our house, and who would eventually become my step-father. My mom and Larry made it into an adventure. “It will be like camping! You’ll sleep in sleeping bags on the floor. And we can go to Thirfty’s and get you some new overalls!” I didn’t cry about how lonely my dad might be until later.

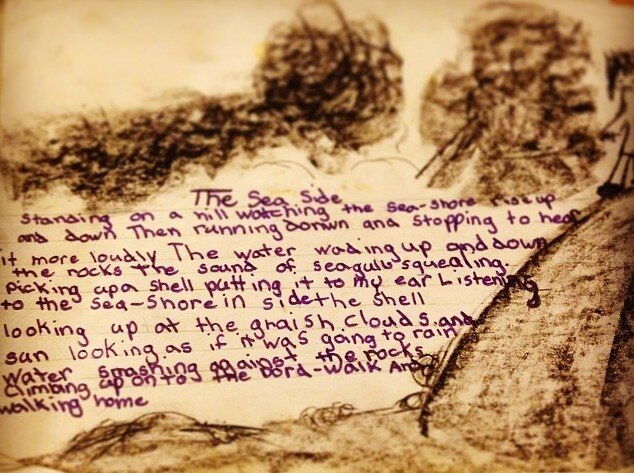

Miss Elkington suggested I copy my poem onto a larger paper and ripped a piece off a big roll. She handed me some charcoal. “You might want to do a drawing to go with your poem,” she said. I felt special because I was the only one that she gave large paper to and allowed to sit in the school hallway to write out my poem. It was a poem about listening to the silence of the sea. I was proud of it. I wrote it as big as I could on the wide page, trying to make my letters neat. I drew the sea beside the words, with whitecapped waves crashing onto the rocks. The whitecaps didn’t turn out like I wanted, they looked more like scribbles, but I was happy with it otherwise. Miss Elkington stood over me looking down at my work.

“It’s beautiful, Abby. Let’s roll it up so you can take it home.” She carefully rolled it and secured it with an elastic band.

In the lunch room later, Cecilia, an older, grade 4 girl with thick glasses, who was in the special ed class, accused me of showing off because I was practicing my cartwheels in the hallway.

“You think you’re so great!” she said.

“No I don’t. I just like doing cartwheels.” I was very scared of her. I knew the other girls in my class were scared of her too. She came and stood inches from my face and shoved me. It was very unexpected.

“Stop it!” I screamed, my hands flailing to try and push her away. One of my hands caught on her classes and they went flying. I watched them skid along the floor in what seemed slow motion. Bouncing off a wall, one of the thick lenses popped out of the frame. I held my breath.

“TEACHER!!” she cried. “That girl just tried to beat me up and knocked my glasses off and now they’re BROKEN!!” She ran over to the teacher on lunch duty, who looked at me.

“Did you do this?” She glared at me and I burst into tears.

“I didn’t mean to.” I couldn’t say anything else to defend myself through my tears. We were both sent to the principal’s office. We sat side by side on the wooden chairs just outside the principal’s door.

“You’re going to be in BIG trouble,” she said. “They can’t get mad at me because I’m in special ed.” I responded with more tears.

“Cecilia, can you come in please?” he said. She turned and stuck her tongue out at me.

A few minutes later, she came out. As she walked past me, she whispered, “You’re in BIG trouble!”

“Abby, can you come in now?”

I sat in a big chair in front of his desk.

“Well, Abby, I’ve called your mother. She’s on her way.” I imagined my mom being very mad to have to leave work to come and get me. I cried more.

“Can you tell me what happened?” The principal said gently. I wiped my tears and sucked in a breath.

“She got mad that I was doing cartwheels. She thought I was showing off. She pushed me, and I pushed back. My hand knocked off her glasses, but it was an accident.”

“Ok,” he said. “That’s fine. I know that Cecelia can be a little… excitable. You just try and stay away from her from now on OK?”

I nodded.

“Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?” he asked. I looked at him blankly. I couldn’t imagine what else I would talk to this man about. I had never spoken to him before. I shook my head.

“OK, well, why don’t you wait outside until your mother gets here, OK?”

I sat for what felt like hours. Lunch was long over and everyone was back in their classrooms.

When my mother arrived, I started crying again. She came and gave me a hug. “I’ll just go and talk to the principal for a minute and then we can go, OK?”

I nodded. She came out of the office a few minutes later. She didn’t look too mad.

“OK, are you ready? Let’s go to your classroom and get your things.”

“OK,” I said.

In Miss Elkington’s class, I felt weird taking my coat and my book bag. All the kids were looking at me.

“Don’t forget your poem,” Miss Elkington said, handing me the rolled up poem. She turned to my mother.

“Abby wrote a beautiful poem today.”

We sat in the car, still in the school parking lot. My mom turned to me. “So what happened?”

I told her the story again. “She’s crazy, Mommy. Really.” I said.

“And nothing else is bothering you?” She looked at me intently.

“No. Why?”

“Well, the principal thinks you might be upset because of what’s happened between your dad and I.”

I was taken aback. My parents hadn’t entered my mind at all. It never really occurred to me that my strange new living arrangement, the walks across the park clutching my three-year-old sister’s hand, telling her it would be OK, that I would be her mommy when we were at daddy’s, might have an adverse affect on me. To me it was an adventure and I got to be grown up and take care of my sister. Except for feeling sad for my dad, I didn’t see it as a bad thing, until now.

“No. I’m not Mommy. You have to believe me. She was just crazy, that’s all. She pushed me because I was doing cartwheels. All the girls are scared of her.”

“OK,” she said, not looking convinced. “Well, I hope you will talk to me if you are having a hard time with everything that’s been going on.”

“OK.” I said.

“So can I see that poem you wrote?”

I unrolled the paper and showed it to her.

“That’s lovely,” she said. “That’s beautiful writing.”

Reading the poem now, I understand the adult’s concern for a young girl whose parents have just split up. The poem is about a lone child who watches the waves roll in, before running down to the beach to listen to the sea “more loudly,” watch the seagulls, pick up a shell to hear the sound of the sea inside. The day is cloudy, about to rain. The poem is melancholy and lonely. But I don’t remember feeling that way when I wrote it. I remember dreaming about seeing the beach, and feeling lulled by the sounds and the calm that I found there. At the young age of 8, I had not yet seen a real ocean and it was something I longed to see.

I must have written more poems in Miss Elkington’s class, but I don’t remember them. No other poems were saved. Somehow, the magic of writing poetry was lost to me that day, though I was never aware of it, nor could have explained why.